Adventures In Urban Sustainability: Ten Years On

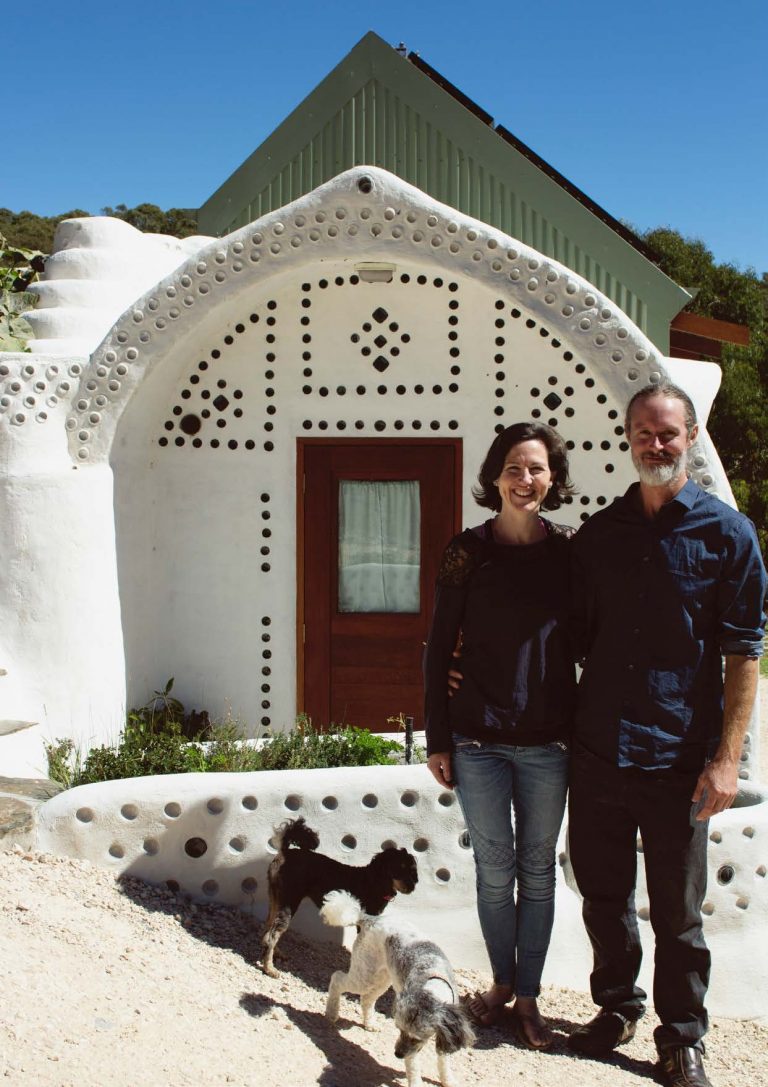

Inspired by their experiences WWOOFING around Australia and volunteering at their local community garden, Alison Mellor and her partner Richard Walter embarked on an urban sustainability adventure. They retrofitted their 1950s suburban house in Wollongong (on NSW’s south coast) and transformed their backyard into a flourishing food garden. Ten years on, they reflect on the design process, the changes they’ve made and the lessons they’ve learned.

In The Beginning

In 2007, we first came across what would become our house and garden. It sat on a north facing 920 m2 suburban block. We saw a blank canvas ripe for creating a flourishing food garden, and plenty of potential to retrofit the small fibro house for sustainability. We spent three months working on the house before we moved in and during this time created the overall design for the food garden.