Nature Kids: Education For Sustainable Living

There is something so absolutely delightful about seeing children play outside in nature, creating worlds and games together, using just the things they can find around them – branches, sticks, feathers, rocks, water – and being totally enthralled for hours.

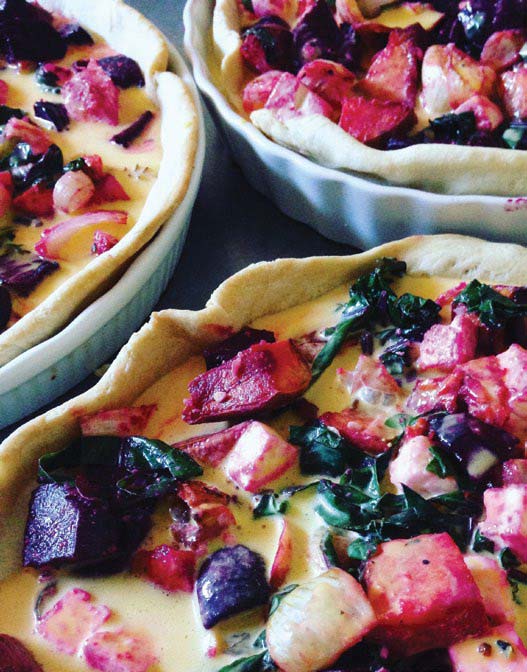

Ask my children where their favourite place is: ‘The river!’, always the river. We often venture down to the river after school with a little picnic, or some things to cook up on a campfire. Our spot is in the upper Mary River – shallow, rocky, shady, cool – a peaceful place in the restored riparian zone of Crystal Waters Eco Village.

The children skim stones, rock hop, find bridges and islands, float sticks and leaves, search for fish and yabbies, make harbours, swim, splash in mud pits and smear themselves from head to toe, climb trees, build cubbies and create complex games. I hear their constant chatter and laughter, and sometimes songs. I notice how intensely productive they are in making ‘things’ for their games. There is real meaning, purpose, creativity and collaboration happening. Deep learning takes place in this play time. They love it so much they even ask for their birthday parties at the river.