Bioregions: Our Spirit Of Place

A bioregion is a geographic area with boundaries defined by natural features such as catchments, soil types, geographic features or vegetation types. Bioregions create a sense of place; where people can identify with their location; in which people can create some form of community self-reliance, producing and trading within those boundaries.

The idea of bioregions appeared in the 1970s, along with permaculture and, like permaculture, bioregions are a way of describing things that already exist but seeing them differently. Bioregions are more easily identified in rural areas, but even in cities, catchments such as the Yarra or the Hawkesbury have distinct bioregional characteristics, as do many suburbs.

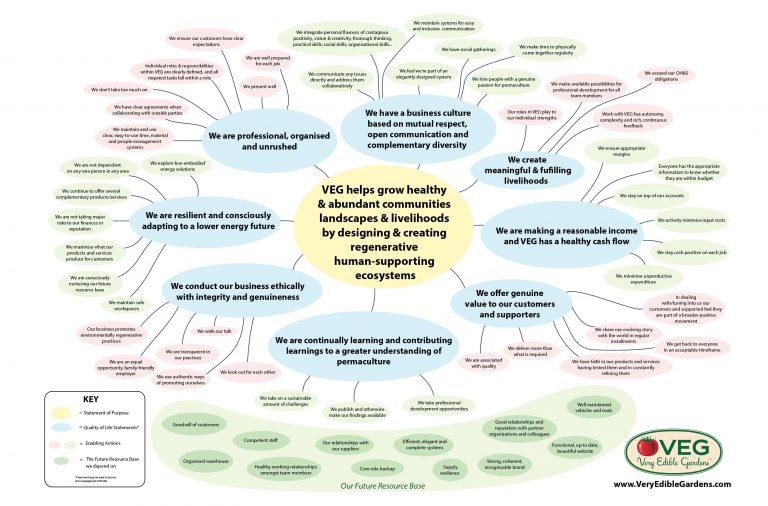

‘Transition Towns’ has emerged over the last decade as a global movement full of practical actions to build resilience in a world threatened by peak oil and climate change. When combined with permaculture principles and the art of reading the landscape, Transition Towns have empowered communities to produce ‘energy descent action plans’, detailed permaculture designs for whole bioregions, not just for a farm or garden.